Sunday, May 16, 2010

Evaluation of our Art & Today Falcilitator Role

Monday, May 3, 2010

Art & Audience

Artists take part in a performance by Surasi Kusolwong of Thailand during the "It's simply beautiful" exhibition at the Center for the Arts and Industrial Creation in Gijon, northern Spain, July 27, 2007.

Artists take part in a performance by Surasi Kusolwong of Thailand during the "It's simply beautiful" exhibition at the Center for the Arts and Industrial Creation in Gijon, northern Spain, July 27, 2007.

Photos of Cynthia Hopkins by Paula Court

from "The Truth: A Tragedy"

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Exhibition View, Secession 2002

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Exhibition View, Secession 2002 Gas station owner recites James Joyce in Harrell Fletcher's "Blot Out The Sun," 2002

Gas station owner recites James Joyce in Harrell Fletcher's "Blot Out The Sun," 2002 Carsten Holler's Test Site at Tate Modern

Carsten Holler's Test Site at Tate ModernPg 392, Heartney refers to early twentieth-century British critic Roger Fry as expressing that the Artist should be thought of as the transmitter, the art object the medium and the spectator the receiver of the meaning of a work of art. " In essence," Heartney says, "the viewer's task was simply to clear away any messy static inhibiting clear reception of the artists ideas." but by the end of the 20th century, the role of the viewer was to complete the work--

Can a piece really be completed by the audience? Is it not already completed in the mind of the artist? What role does perception play?

Are art projects created in the spirit of community activism really art?

How does gift sculpture create interplay with the artist and viewer in the artwork? What is the outcome?

Saturday, May 1, 2010

Art & Spirituality

Yves Klein, Cosmogonie, 1960

Watercolor, leaf, and twig print

Yves Klein immersed himself in the reading of Max Heindel's Cosmogonie des Rose-Croix and himself wrote of and created images that reflect his interest in emanation, enveloping atmospheres, invisible radiance, ecstasy, the abolition of movement, and the vaporization of the self (from Yves-Alain Bois, Klein's Relevance for Today).

See more Cosmogonies ....

*Image from Ein Bildhandbuch: Staatliche Graphische Sammlung Munchen, 2002

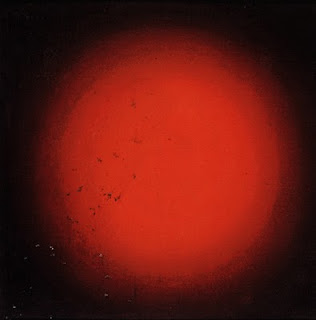

Ivan Kliun, Red Light, Sherical Composition, 1923

Ivan Kliun, Red Light, Sherical Composition, 1923 Wassily Kandinsky. Several Circles. 1926. Oil on canvas. 140 x 140 cm. The Solomon R. Guggebheim Museum, New York, NY, USA.

Wassily Kandinsky. Several Circles. 1926. Oil on canvas. 140 x 140 cm. The Solomon R. Guggebheim Museum, New York, NY, USA. Francis Alys, When Faith Moves Mountains, 2002

Francis Alys, When Faith Moves Mountains, 2002 Anish Kapoor

Anish KapoorBlackness from Her Womb

2001

Can we ever really separate art and spirituality? Would we really want to. For me spirituality is the essence of why I make art-- trying to have a deeper connection/ understanding of self related to the whole-- the bigger picture is what motivates me..

pg 266, Heartney is saying that religious imagery held sway until the birth of modernism in the late 19th century-- the alliance of western art and religion fell to pieces because of identification with organized religion with reactionary and authoritarian forces that were being overthrown everywhere-- so out with the old orthodox system, but still creating rhetoric of transcendence and spirituality, creating a vision of art as a sacred practice unto itself.

This is the point of entry when the thought of displacing the spiritual experience through religion changed to experiencing spirituality as an individual level. Have artists really ever been separate from the individual experience of spirituality? relating to my question above, Are we not always trying to search for the answers of who we are through making art?

The freedom artist felt with the split from religion led to abstraction-- Is abstract art the way to a spiritual experience through color and form?

Do artists like Trenton Doyle Hancock who have a deeply rooted background in organized religion have a better chance of transcendence through their practice?

RB Kitaj and Archie Brand use colors that remind me of Kandinsky's color choices-- Is color a way to express spirituality?

Heartney says on pd 281 that for many artists, like Boonma and Mendieta, religious traditions serve as vehicles for spiritual exploration. Is this a form of homage or just a toolbox used to express this exploration?

Questions from Lili:

Eleanor Heartney starts her chapter on Art and Spirituality discussing the split between art and religion in the late nineteenth century.

Is there a difference between spirituality and religion? How do you define spirituality? How do you define religion?

Yes! What I discovered through the readings is that a bucking of the authoritarian systems of organized religion led to a spiritual awakening on an individual level-- Abstraction is a direct result of this chasm.

Spirituality is a deep connection to understanding self and religion is a fear based institution.

Do art and spirituality ask the same fundamental philosophical questions (i.e. why are we here, what is the meaning of life, do we have a purpose) and is the truth they are seeking the same truth? Is it possible for art and the artistic process to be split from spirituality?

These are fundamental questions I have been asking myself and I really do believe art, art-making and spirituality and interconnected asking the same questions and the truth is the same truth-- I do not think they truly can be split-- if one thinks they can there is a layer of illusion present.

Religious symbols are a powerful statement when used artistically. Do they take the viewer out of the work and back into the world, as Kandinsky proclaims, and prevent the viewer from finding the inner truth in the work? I am not sure-- I can relate to Kandinsky's conversations about how color like yellow draws you away from center and blue takes you toward center.

Can the inner spirit, or soul, or consciousness or truth be manifested in the artwork without resorting to the use of the symbols and beauty, etc of the material world? If so, how? Could someone answer this for me?!?!?! I have been grappling with these issues in my own work

Can a work of art transport the viewer into a spiritually altered state of consciousness? Kandinsky writes about a spiritual vibration that comes through the work and becomes the inner value of the work. Is there such thing? YES! Maybe not all will experience it but I believe it is so.

“The work of art is born of the artist in a mysterious and secretive way. From him it gains life and being. Nor is its existence casual and inconsequential, but it has a definite and purposeful strength, alike in its material and spiritual life. It exists and has the power to create spiritual atmosphere; and from this inner standpoint one judges whether it is a good work of art or a bad one.” Can an artwork be judged based on its ability to ‘speak to the soul’ as Kandinsky writes? In my humble opinion-- for me, this speaking to the soul is the primary reason for viewing art.

Can making a work of art transport the artist into a spiritually altered state of consciousness? Can the work portray the spiritual journey of the artist to the viewer on a spiritual level? One can hope.

How does Kandinsky’s essay relate to Walter Benjamin’s article read earlier in the semester called Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction and his theories on whether art has an aura?

Is consciousness the same as spirituality? The same as the soul?

| AWESOME ARTICLE for your reading pleasure... "Art is the daughter of the divine," contended philosopher Rudolf Steiner in the 1920s. Most art 1overs today would assume that Steiner was referring to a pre-20th-century past. True, art was once the daughter of the divine, they might say. But in the 20th century the once-dutiful daughter has struck out on her own, ignoring her religious heritage (indeed, ignoring religious subject matter altogether) and turned her attention to form. Abstract art is a purely aesthetic activity. Certainly in the late 20th century, it is rarely associated with religion. However, in recent years this story of abstract art has begun to undergo revision. Art critics have discovered that for many artists, abstraction is a way not to express emptiness but to communicate particular ideals. A number of major exhibitions exploring the roots of abstract art have emphasized artists’ utopian hopes bred by the industrial revolution, or their revolutionary political thought, or their revival of primitivism out of a dissatisfaction with the modern world. The latest of these exhibitions appeared in Los Angeles and Chicago during the first six months of this year: "The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985." (It is on view at the Gemeetemuseum in the Hague from September 1 through November 22.) While the exhibition leaves intact the notion that the "daughter of the divine" has indeed struck out on her own, it offers an intriguing challenge to the widespread belief that she has altogether abandoned her spiritual focus. Rather, like many adventurous spirits through history, and a fair number of seekers during our own age, she has shunned traditional religious expression in favor of esoteric aspects of spiritual life. For those able to accept a broad definition of the word "spiritual" -- one that encompasses elements of the mystical, the gnostic, Eastern religions and the occult, and has few, if any, discernible connections with the Hebrew or Christian Scriptures -- abstract art might be approached as a doorway to the symbolism of modern culture’s spiritual underground. In any case, the arguments advanced by exhibit curator Maurice Tuchman and others in the exhibition catalogue (copublished by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Abbeville Press, New York) deepen our appreciation not only of abstract art but of a little-understood aspect of the religious temper of our times. To understand the daughter’s journey, it is helpful to recall the break with traditional religious art that took place in the Romantic period. Friedrich Schleiermacher gave theological impetus to highly privatized religious forms with his Romantic insistence that inner piety is more important than outer forms. "Indeed," argues Robert Rosenblum in Modem Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (Harper & Row, 1975) , "Schleiermacher’s theological search for divinity outside the trappings of the Church lies at the core of many a Romantic artist’s dilemma: how to express experiences of the spiritual, of the transcendental, without having recourse to such traditional themes as the adoration, the Crucifixion, the Resurrection, the Ascension, whose vitality, in the Age of Enlightenment, was constantly being sapped." Rosenblum, an art historian invoked in one of the catalogue essays, was among the first scholars to assert that abstract art, far from representing a neat break with representational art, is actually part of a Romantic tradition reflected in northern European artists like Caspar David Friedrich and Joseph M. Turner, who infused landscape paintings with a "sense of divinity." Abstract artists faced the same problem as the earlier Romantics, he said: "how to find, in a secular world, a convincing means of expressing those religious experiences that, before the Romantics, had been channeled into the traditional themes of Christian art." According to art historian Charlotte Douglas, the shift to abstract art in the early 20th century was prompted by a need for new dimensions of consciousness, forms suited "to serve as a passport to and report from" the so-called higher realms. Esoteric cousins of theosophy that attracted the artists featured in the exhibition include Rosicrucianism, alchemy, Tantrism, cabalism and Hermeticism. The writings of psychiatrist Carl Jung, who was himself interested in alchemy, parapsychology and the occult, were a favorite of some artists. Others favored Jacob Boehme, the 16th-century Lutheran shoemaker who combined Neo-platonism, the Jewish Cabala and Hermetic writings and the Bible in explaining his experiences of God. Still other artists made use of symbols from medieval legends, Hinduism, Zen Buddhism, the religion of American Indians, the teachings of G. I. Gurdjieff and the works of medieval Christian mystics such as Meister Eckhart, John of Ruysbroeck and Richard Rolle. That theosophy and other types of occult and mystical thought have influenced abstract artists is supplemented in the show by 125 books by theosophers, philosophers and mystics whose images and ideas also appear in the tradition of abstract art. The argument for the relationship begins with four artists generally viewed as pioneer abstractionists, all of whom are shown to have been steeped in spiritual concerns. Piet Mondrian, the Dutch painter best know for his abstract gridwork of interlocking perpendicular black lines and enclosing squares of red and yellow, was an avid reader of theosophy, who once said he learned everything he knew from Madame Blavatsky He joined the Dutch Theosophical Society in 1909, about the same time that his work began its gradual evolution toward the abstract. The shift was heralded in his landscapes: wide expanses of beach and sea; forest scenes that highlight the vertical thrust of trees from a horizontal expanse of earth. Mondrian’s preoccupation with the tension between vertical and horizontal was later depicted in the haunting abstract cruciform patterns that would become his trademark. One critic has said that given the antisocial attitudes apparently underlying abstract works, a viewer unfamiliar with Mondrian’s personal religious quest might associate his grids with jail bars. But according to Mondrian’s own notebooks, the patterns represent the struggle toward unity of cosmic dualities and the religious symmetry undergirding the material universe. A strong believer in the theosophical doctrine of human evolution from a lower, materialistic stage toward spirituality and higher insight, Mondrian wrote that the hallmark of the New Age would be the "new man" who "can live only in the atmosphere of the universal." For Wassily Kandinsky, the religious themes implicit in his paintings are made explicit in Concerning the Spiritual in Art, a little book he wrote in 1910, the year he did his first abstract painting. Kandinsky, like many abstract artists, saw himself as a spiritual as well as an aesthetic pioneer. Like Mondrian, Kandinsky was versed in theosophy, and felt that abstraction was the best means available to artists for depicting an unseen realm. With near-messianic fervor, Kandinsky announced that the type of painting he envisioned would advance the new "spiritual epoch." In his book he describes the spiritual realm as a triangle in upward motion. At its apex stands a man whose vision points the way; within are artists, who are "prophets," providing "spiritual food." Familiarity with this theory is all but crucial to understanding a painting like Kandinsky’s "Variegation in the Triangle." This 1927 work consists of an obtuse triangle set against a background of dense clouds that seem to be in motion. At the apex of the triangle is a circle, a symbol of wholeness and unity in much mystical thought, and within the triangle are circles connected by straight lines, likely representing the artist-prophets. Two other pioneers, Frantisek Kupka, a Czech, and Kasimir Malevitch, a Russian who in 1914 and 1915 exhibited a series of squares on plain backgrounds, were also avid readers of theosophy and other metaphysical works. Kupka studied Greek, German and Oriental philosophy, along with a variety of theosophical texts. Douglas writes that the aesthetics of Malevich and his circle "resulted from a unified world view that encompassed all dichotomies; for them science and Eastern mystical ideas were seamlessly joined in a conceptual continuum, and knowledge of the world might be obtained by beginning at any point." Tuchman stresses that it was not just the founders of abstract art who were interested in spiritual investigations. "Abstraction’s emergence throughout the 20th century was continually nourished by elements from the common pool of mystical ideas." What artists found appealing about the various arcane religious and philosophical systems was their underlying premise that the spiritual world is governed by laws that mirror natural laws and that can be expressed in symbols. The idea is akin to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s notion that every appearance in nature corresponds to some state of mind. Geometric forms are thus paradigms of spiritual evolution. The spiritua1 world, like the natural world, is charged with energy, producing cosmic vibrations and human auras. The spiritual principles that intrigued certain artists included synesthesia, the overlap between the senses by which a painting can simulate music; duality, the idea that the cosmos reflects an underlying principle of yin and yang; and so-called "sacred geometry," the belief that, as Plato put it, "God geometricizes." Against this background, the works take on new meanings. For example, the Russian Ivan Kliun’s work titled "Red Light, Spherical Composition," which portrays a hazy red-orange sphere against a black background, bears a striking resemblance to Fludd’ s mandalas. Yves Klein’s "Cosmogony" is a canvas covered with blue, red and black circles that seem to be in movement, as if engaged in a cosmic dance. The works of Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) , an early American abstractionist who was an avid reader of Christian mystics, combine symbols from traditional Christianity and the occult. Hartley once said that it was "out of the heat of his reading" of the mystics that he began his works. In "The Transference of Richard Rolle" (1932-33) Hartley pays tribute to that 14th-century English mystic. The painting is of a cloud, set against a deep blue sky and hovering over a barren red-rock landscape. The cloud is imprinted with a yellow triangle enclosing Rolle’s monogram, suggesting transcendence within the Trinity. And the use of American Indian pictography by Jackson Pollock and others indicates the interest in the 1930s and ‘40s in the vitality and spirituality of Indian culture. As the century wore on, some artists abandoned the search for iconography and turned to more radical abstraction. Viewing the exhibit, I found it especially fascinating to ponder some of the purer abstract works -- such as the rich, dark, imageless canvases of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko -- in relation to the apophatic tradition in Christian mysticism. Masters of that tradition, sometimes called the via negativa, choose words like nothingness, darkness and obscurity to symbolize God, the wholly other Absolute who is unknowable by means of the intellect but approachable through love. Newman’s and Rothkos somber, borderless canvases suggest deep silence and infinite void, yet somehow, too, evoke a sense of presence and mystery. Newman, an American who died in 1970, made no attempt to hide his spiritual interests. In 1943 he wrote, "The painter is concerned . . . with the presentation into the world mystery. His imagination is therefore attempting to dig into metaphysical secrets. To that extent, his art is concerned with the sublime. It is a religious art which through symbols will catch the basic truth of life." For many Christians, the theme of the show is sure to be problematic, perhaps rightly so. Scrutiny of the artists’ sources reveals a deep immersion in multiple forms of Neoplatonic spirituality -- a spiritual pursuit that has accompanied Christianity from the time of Irenaeus, who thundered against the gnostics in the second century, to the present, a time in which ultraconservative Christians view the occult as a direct manifestation of evil spirits. The dangers of a spirituality divorced from the disciplines and dogmas of established religion have always been clear to Christian leaders. One is reminded of St. Paul’s admonition to "test the spirits." On the other hand, this reading of abstract art offers yet more evidence that the religious landscape has undergone radical shifts. In their new book American Mainline Religion: Its Changing Shape and Future (Rutgers University Press, 1987). Wade Clark Roof and William McKinney note that traditional Christian symbols can no longer be relied on to forge a synthesis of religion and culture. They cite a need for a new mode of synthesis, one suited to a post-Protestant age. Seeing the connection between abstract art and spiritual exploration is sure to contribute to a better understanding of the metaphysical quests taking place on the fringes of our culture. Though these quests undoubtedly are alien to many, they are rooted in intellectual currents that arose more than a century ago and have never disappeared. |